As any reader of our local history section will know, our borough has had more than its fair share of fascinating characters and interesting tales. From daredevil pilots to royal molecatchers, and from manor houses to music stars, there is a rich past to dip into.

In the coming weeks, 3 local history talks will shine a light on some more. They will all be held at Ealing Central Library at 5:30pm.

True crime inspirations of Agatha Christie

Borough archivist Dr Jonathan Oates will give this talk on 19 February.

Agatha Christie is well known for her detective story fiction, novels, plays and short stories featuring Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple and others.

But did you know that she also included many references to real killers, fraudsters, kidnappers and spies in her fiction?

Or that some of the best-known books had back-stories which were inspired by true crimes?

Explicit and implicit references are made to at least 40 true crimes. These are less known now than they were.

However, Murder on the Orient Express has the infamous kidnapping and murder of the young Charles Lindbergh as the basis for the background to this tale of retribution. The Mousetrap has the appalling abuse and death of children in the 1940s as the inspiration for the backstory which provides the killer with their motivation.

Other real criminals such as Dr Crippen, Major Armstrong, the Brides in the Bath serial killer and Jack the Ripper also feature in these stories. Many not versed in true crime history may not know of Lizzie Borden, alleged axe murderess; or Madeline Smith, accused of poisoning her lover. Both are mentioned several times in the books and the former may be an inspiration for a character in And Then There Were None. Sometimes, these killers and their activities are compared to fictional counterparts and sometimes plots are similar to real life crimes, which are not always made explicit.

This talk will outline some of these real-life criminals and their use in the fiction, which show that Agatha Christie was not only a master of fiction but was also historically literate as regards crime history.

Frank Bowcher: the Ealing connection

On 26 February, Philip Attwood will talk about Frank Bowcher.

Best-known as a prolific maker of medals in the early 20th century, Bowcher (1864-1938) was also a sculptor whose works can be found in the UK (including Westminster Abbey) and India.

Living in nearby Bedford Park, Bowcher had a long association with Ealing, receiving commissions for memorials to be placed in Ealing Town Hall, Pitzhanger Manor and elsewhere. His sculpture of Ealing architect and borough engineer Charles Edward Jones can still be seen in Walpole Park, but other works, of Thomas Huxley and Edward VII, have mysteriously disappeared.

This talk will discuss this talented artist’s connections with Ealing and ask where those sculptures, once highly prized, can now be found. Two of the buildings – the King Edward Memorial Hospital and the former Thomas Huxley College – in which these sculptures were located were demolished decades ago.

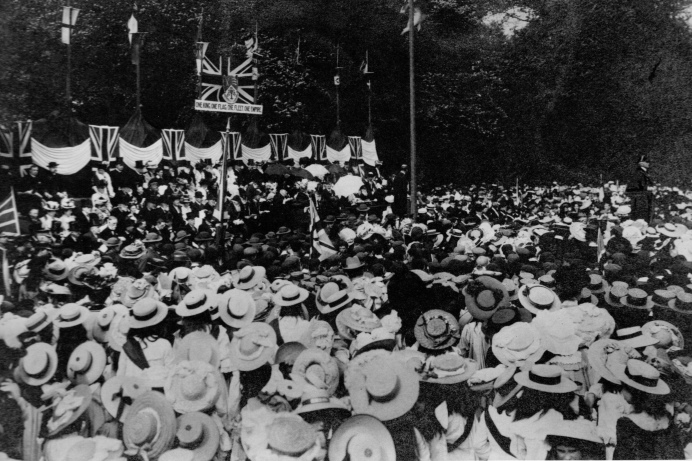

Empire Day in Ealing, 1905-1959

On 19 March, Dr Jonathan Oates and Elisia Swaby will give this talk.

Now almost completely forgotten, on 24 May Empire Day was celebrated in Britain and elsewhere. This talk looks at how this day was celebrated in Ealing.

It was primarily aimed at schoolchildren and typically schools would devote the morning to lessons and songs about the British Empire. There might be an outside speaker with firsthand experience and knowledge. The afternoon was then given over as a holiday. The day was chosen because it had been Queen Victoria’s birthday.

Although there seems to have been no celebrations in Ealing in the year of its inception, there were major activities in Walpole Park in the years immediately thereafter.

Emphasis changed over the years. In the 1930s peace and brotherhood of nations was stressed at a time when global conflict was feared. Businesses tried to use the day to promote products that had been imported from the Empire and Commonwealth. The Conservative Party also used the day to rally their supporters, though it was envisaged as not being party political.

There was also dissension, with the Southall branch of the Communist Party attacking the concept of the day and holding alternative events. This caused controversy locally. Reflecting political realities, Empire Day was transformed into Commonwealth Day in 1959, but there was less enthusiasm for this and most would now not know it existed.