October is Black History Month. In the first of 2 local history articles this month, borough archivist Dr Jonathan Oates looks at a groundbreaking bookshop.

In the 1960s, and later, it was difficult to buy books in the UK about black history and culture for both adults and children. In 1966 the first British black book publisher was founded: New Beacon Books. And, in 1967, there was another, Allison Busby.

The third was Bogle L’Ouverture Publications Ltd in Ealing when, in 1968, Jessica and Eric Huntley founded the company, and later a shop.

Initially known as Bogle L’Ouverture, the shop was one of the first places in Britain where books discussing black history, politics and culture could be bought, when mainstream bookshops did not stock these.

It became a focus for black activists and for numerous meetings and educational activities in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it faced challenges, both from town planning officials and from racists.

The story begins

The bookshop was named after Paul Bogle, who led a rebellion in Jamaica in 1865 and Touissant L’Ouverture, who was a black general in Haiti who opposed the Spanish and French in the Haitian wars. These names were suggested, respectively, by Richard Small and Chris Le Maitre.

The original intention was not to establish a book shop. In retrospect it was stated ‘Bogle L’Ouverture Publishing was born as a direct result of the political act of the Jamaican government in the banning of Brother Walter Rodney from re-entering Jamaica in 1968’. The origins, therefore, were born out of a form of political protest. On 15 October 1968 the Jamaican government barred Dr Walter Rodney from re-entering Jamaica. Rodney was a Guyanese lecturer in African history at the university of the West Indies. He also held classes in the history of black civilization outside the classroom and had recently attended a writers’ conference in Canada.

His being barred sparked off protests in Jamaica and elsewhere. In Jamaica, workers in Kingston as well as students from the University of the West Indies, protested in the streets. They were met by the army and police and three people were killed. The formal political opposition did not lift a finger and there were curfews. In London, the Jamaican High Commission was blockaded and there was a sit-in in the Jamaican Tourist Board offices.

It was in response to these events that a group of expatriate black people met in 110 Windermere Road, South Ealing, which had recently been moved into by the Huntley family. Amongst those gathered there were Andrew Salkey and the Huntleys.

Jessica and Eric Huntley were born in Guyana in 1927 and 1929 respectively and arrived in the UK in the 1950s. There were also their sons, Chauncey and Karl Huntley, and then Accabre, born in 1967, at this address. The meeting decided that to support Walter Rodney, and that his works – speeches and writings – should be made available to a far wider audience because many people only had the official point of view. Rodney travelled to Tanzania and, en route, he let his supporters have copies of his papers. These were read and the desire to publish was established as a way of continuing the political struggle.

Finding a way

It needed more than good wishes, however. Meetings were held and money had to be raised. Jessica contacted friends to ask for loans and donations. Money was also raised by social events and dances. The dining room and the sitting room of 110 became the nerve centre of this new publishing venture. In June and July 1969 work started on the first book and, as one observer said: ‘We were excited like chicks, each one of us wanting to finger and launch the finished product’.

The book was titled Groundings with my Brothers. It contained speeches and lectures by Walter Rodney concerning Black Power, Africa’s history and civilization, its great leaders and Black Revolution. Errol Lloyd designed the dust jacket. The first print run was 3,000 copies.

From there the venture grew. It was more than a bookshop, and in fact that term is probably quite misleading, at least to begin with. It was founded as a publishing house, publishing books exclusively by young black authors and writings for publication by any black author from anywhere were welcome.

School text books was another major part of their work as well as books for adults about politics and philosophy, among other topics. One of the first works of fiction was ‘One Love’, published in 1971, edited by Andrew Salkey. This was an anthology of writings about love between black people. Its authors included Pam Wint, Audtil King, Althea Helps and Frank Hasfal.

Posters and greetings cards were also sold. The posters included Mother and Child, and Self Portrait Rastafarian by Ras Daniel. They were 12 differently designed greetings cards designed by Errol Lloyd, Lena Charles, Kofi Wilkins and Emmanuel Jasper.

Financial resources were meagre and it was a case of living from hand to mouth. In 1971, letters were written to potential donors, asking for £5 each in order to reprint Groundings and publish another of Rodney’s books. There were some cash contributions from other black people.

Proceeds from parties helped. Royalties from the Groundings with my Brothers were fed back into the not for profit organisation, except for royalties from European sales which would go to the author. Likewise, authors Phyllis and Bernard Coard gave royalties back. Sybil and Joe Phoenix gave a loan of £1,000.

However, overheads were very low and in 1970 staff were all volunteers. Some white people helped, especially a printer who offered capital in exchange for becoming a partner. Others who helped were Frank Fraser with legal skills and Sister Venetta Ross.

Eric Huntley looked back in 1987 about their work. The last thing on their minds, he stated, was to make money. He said: ‘As making a profit was not really our main concern we were regarded like a social service’.

Rain Falling, Rain Shining by Odette Thomas, a Trinidadian born in 1951 and living in America, was one of the first children’s books to be published. It contained rhymes to be read and said to children.

The 4 Huntleys and their business moved to the front room of 141 Coldershaw Road in West Ealing in 1972, the house where they now lived.

Until 1973 they were publishers only; in that year the sale of books directly to customers began; mostly mail order. 141 Coldershaw Road was now open to individuals and small parties from Monday to Friday at either 10am or 6pm. Some were from teachers and librarians, ‘many of whom expressed an interest in books about and by black people, but did not know where to obtain some’.

Hitting trouble

It was there that it ran into its first set of problems: planning inspectors. In 1975, a council inspector explained there had been no permission sought for the property’s change of use, from a residential to a business premises and so an enforcement notice had been served. This led to a public inquiry at Ealing Town Hall that year and an inspector from the Department of the Environment was present. Apparently, neighbours were concerned that house prices would fall and the standard of the residential street would deteriorate. The Huntleys found this news shocking.

Jessica told the inquiry that she was providing a much-needed service to ‘help West Indian and third world children’. There were only 2 such services in the country. She also said that the activity had never been a public nuisance and there had been no complaints from the public about it. Her work was voluntary and unpaid. There were no business overheads and all profits went to the publishers and authors.

Cris Le Maitre was a legal representative from the Ealing Community Relations Council and he was there to help Jessica.

Jessica said that other premises had been sought but without success, and trying to find mainstream bookshops to stock its books had been met with ‘a very negative response’.

Groups of school teachers and children had also been in numbers, but there were no regular visits. Delivery vans did not cause obstructions in the streets, and the front room in question was for display purposes.

Yet, for all the claims that no one had complained, there was a Mr P. Jackson of 137 Coldershaw Road. He said that he objected because if this business was allowed, then it could lead to others doing so and so making life more difficult from residents there like him. He also did not like the delivery vans that sometimes were seen outside the house.

The inspector did not dispute the usefulness of the place and its service to the community. He contested the loss of residential accommodation to a shop, and that it set a precedent for other businesses to be established in nearby streets. It was said that the council could help in finding alternative accommodation or that the Secretary of State could give 6 months’ grace to find another venue.

Jessica said: “We are looking for an alternative place, but it is very difficult.”

Sympathy for the Huntleys came from an unexpected place. The Surveyor magazine (for planners) stated: ‘This is not what planning is all about and it is exactly the sort of case that gives planning a bad name’. They thought that the government inspector had been unfair.

Support also came from some local teachers. They argued that because of the stock that could be bought from there, books were gradually finding their way into school libraries that reflected the needs of a multi-racial society. Ther curriculum was evolving to meet such needs. Parents and children enjoyed stories from different cultures that they were discovering for the first time.

A new era begins

A new premises was found, at 5a Chignell Place, a former dress shop, just north of Uxbridge Road in West Ealing and just a few minutes’ walk northwards from the Huntley’s Coldershaw Road home, so very convenient.

This led to major changes in the whole outlook of the enterprise. At 141 Coldershaw Road, the premises had been cramped but overheads were low and only one full-time paid employee was needed. The Chignell Place site was larger and, as a conventional commercial premises, it meant that trade could increase because public exposure had risen. It did mean that more stock and more staff would be needed. It is from this time that the term bookshop can be properly used.

It was from here that the place’s role began to expand. The shop opened in October 1975. School visits were held there and poetry readings took place to help raise money. From May to July 1976, a series of weekly seminars were being held there. These were introduced by Caribbean music and a history of slavery. Each seminar focused on a different urgent social issue and the format included poetry, dramatic readings, lectures and music. The topics included discussions of art, drama, literature, poetry, education, unemployment, the police and the citizen, the legal system and the courts. The first seminar was led by Linton Johnson, a Jamaican born poet and activist who had resided in London for many years. One of his first works was published by Bogle L’Ouverture in the previous year, Dread Beat An’ Blood.

There were also meetings of teachers and children, giving them opportunities to meet outside the classroom to discuss matters of mutual interest. Schools involved were Featherstone Road School and the Pathways Centre in Southall, Faraday and Twyford schools from Acton. Jessica said ‘We want to be an educational centre, not only for West Indian community, but for teachers and white children’.

In 1977 they stocked publications from the Commonplace Workshop including The Other Gazette, a bi-monthly alternative newspaper to the Ealing Gazette.

‘We are not going to be terrorised’

There was another danger to the bookshop. Between 1977-1981 there were 7 recorded attacks on it. These included windows being broken, graffiti daubed on it and offensive leaflets and threats being made.

Apparently, 1977 was worst, with Jessica recalling ‘one lived in fear, not knowing what to find on arrival at the shop’. In October 1979, racist slogans were painted on the exterior. Later that year a threatening letter came, purportedly from the KKK: ‘You have been warned persistently that your presence is not wanted in Ealing, to no avail. Therefore our members have been instructed to take more permanent measures. You have been warned…’. It allegedly came from the Imperial Palace of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan of Atlanta, Georgia. Jessica said that this was ‘part of a pattern of racist and fascist attacks on the shop and not only on the bookshop but on the whole black community’. She was defiant, ‘We are not going to be terrorised’. Eric added ‘There are plans to destroy the place in a more permanent way’.

It is worth noting that at this time, there were other acts of vandalism elsewhere with similar graffiti and even arson. Yellow paint and KKK stickers were daubed over buildings.

They were taken so seriously by the victims that they demanded a meeting with the Home Secretary. There had been 4 such attacks that same year. Jessica met with other bookshop owners in London to form a committee to fight the attacks.

She said: “These attacks on black bookshops are part of a pattern of racist and fascist attacks that have been unleashed on the black community for some time. We know that extreme right-wing organisations are trying to intimidate organisations like ours so that we will close down. But we are not going to close, we are going to fight.”

There had been earlier requests to see the Home Secretary but these were turned down. Now, 10 other bookshops in London had signed a joint letter making the same request. There were also calls for the police to step up their activity and arrest the culprits. Ealing Council had similar concerns.

Council leader at the time, Michael Elliott, had held a meeting of the council to see if they could ask for a Home Office investigation into any other similar attacks nationally. Elliott thought ‘we are not dealing with incidents by vandals or the odd individual.’

Other attacks occurred and there was criticism of the police.

In 1983 there was more daubing of slogans on the shop, this time with red paint. This time the National Action Party claimed responsibility. Jessica said: “I have never heard of this group, although everyday I come to work I expect something like this. I am not worried, just very angry. It just shows the kind of world we live in.”

She was more concerned that there might be an arson attack when someone might be inside. The final recorded attack, the 11th in total, was in January 1983 when windows were smashed to the damage of £300, prompting Eric to say: “We will not be terrorised out of existence.”

There was a public meeting in the town hall shortly afterwards. This was to discuss the attacks and to call for police action. No more attacks occurred.

A change of name

In 1980 the bookshop was renamed after Walter Rodney, the man who was the inspiration for it. In 1980 he was assassinated by a car bomb, possibly the work of the Guyan government. Rodney was a close friend of the Huntleys and Jessica begged him not to return to Guyana and they argued about it in the dining room. As said, 2 of his first books had been published by Bogle.

In March 1991 the enterprise seemed to come to an end, with closure. Although, it was not really the end because the phoenix arose from the ashes to continue again throughout the 1990s. New blood came along to take over.

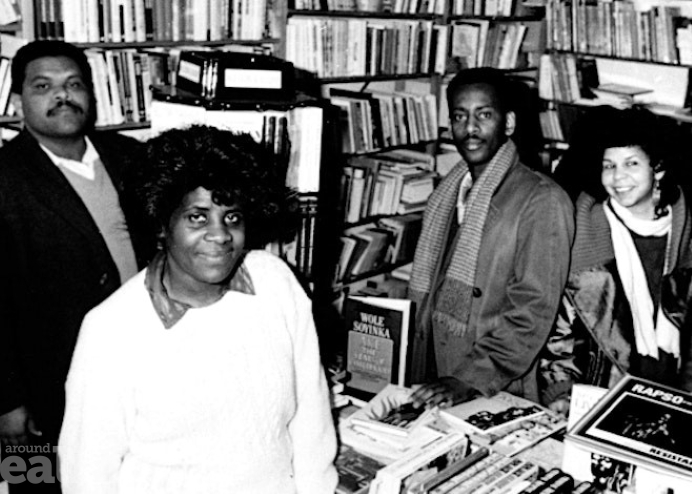

These people included Chris Woodley as editorial consultant for the adult books, who would read manuscripts submitted for publication, and Val Bloom, likewise for the children’s books and poetry. Tok Williams and Henry Golbourne, who was the consultant for non-fiction, were also involved now. The business was relaunched at Shepherd’s Bush Library in July 1993.

Some of the new works included No Tears in Paradise, Two Lives: Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale; History of the Negro – 50 years on, From Negro to Black Africans and Black Women. Beryl Gilroy’s book, Black Teacher was reprinted. A series of biographical studies was planned, with emphasis on having more women featured. Books for community and supplementary schools, aimed at 10-12 year-olds were another line. These would include information about black entertainers and sports stars. One work published was Lucy Safo’s Cry A Whisper, which won the Commonwealth prize for first book in 1994.

Recognition from the wider community

In 1998 during Ealing Council’s first Windrush celebrations for the 50th anniversary, a bust of Jessica, by Jamaican sculptor George Kelly, was unveiled at Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing. She was celebrated for her key role in what was said to be the first black British publishing house.

In more recent years, the enormous Huntley archive has been deposited at the London Metropolitan Archives in 2005. There is even a room in the London Metropolitan Archives named after the Huntleys and with material about their lives and work in the walls. A plaque by the Friends of the Huntley Archive has been put on the house in Coldershaw Road, where the business operated from in 1972-1975. This was in October 2018, five years after the death of Jessica.

In the field of black publishing and writing, Bogle L’Ouverture had a prominent part to play, not just locally but also nationally and internationally. It was a small-scale enterprise but did grow and, for just over 2 decades did more than publish books, as important as this was. It had grown out of political struggle and retained its ideological principles as well as having to adapt to an extent to the marketplace. It was, therefore, also a gathering point for like-minds and was able to project on the wider stage.

In fact, perhaps it was a victim of its own success. In the 1970s books about black history and culture were impossible to find in mainstream UK bookshops but, by the 1990s, this had changed. What had once been extremely rare had now become part of what was seen by wider society as accepted and normal. Specialist shops were perhaps no longer needed to cater for what was now a wider demand. However, for 3 decades it had shone a light for others to follow and its legacy lives on today both on paper in the archives and more importantly in people, those both involved in it and those who have benefitted since.